Highly respected economist, academic and businessman Mohamed A. El-Erian recently penned an editorial entitled “The Fed’s Fixation on a 2% Inflation Target is Risky”. He argued the Federal Reserve was too rigid in its commitment to the 2% inflation objective, evidenced by Chairman Powell’s refusal to reconsider the target during the Fed’s periodic review of the effectiveness of its communication, strategy and policy tools in fulfilling its dual mandates of price stability and maximum employment. El-Erian further explained that the world economy has evolved from multi-decades of “positive supply shocks” caused by the collapse of the USSR, China’s entry into the global economy, etc., to an era of more frequent and intensifying “negative supply shocks” (pandemic distortions, geopolitical conflicts and fragmentation of global trade and cooperation). He contended that such blind adherence to the 2% inflation target could constrain the Fed’s flexibility and risk damaging the US economy, unleashing unintended consequences.

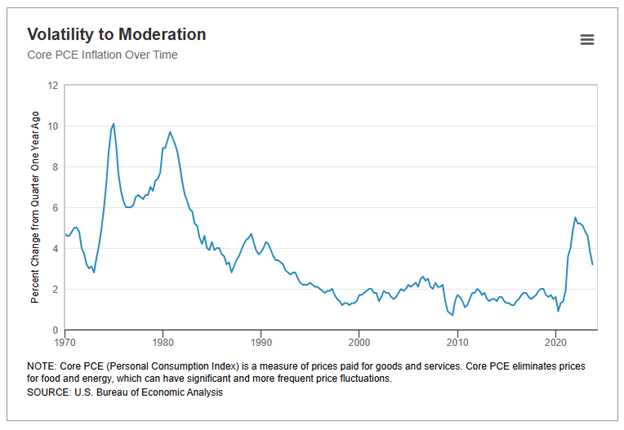

The Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target may seem like long-standing dogma to most, but its history is rather new. Most recently, the Fed has made significant progress in reducing the inflation rate (using PCE or personal consumption expenditures as its preferred measuring stick), lowering core PCE from nearly 5.6% in February of 2022 to 2.65% most recently. But 2.65% remains stubbornly above 2% and worries about the potentially inflationary effects of tariffs could reverse the downward trend. Moreover, the 2% target has a surprisingly contentious history, so El-Erian’s most recent criticisms are nothing new.

What may surprise many is that the 2% inflation target was not made explicit by the Federal Reserve until 2012, after decades of internal debate and outright secrecy. The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 officially established price stability as part of the Fed’s mandate, adding to the existing mandate supporting full employment. Inflation raged during the late 1970’s, reaching double digits. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker applied “tough medicine” in the form of steep interest rate hikes, reducing inflation to 3.2% but also precipitating an economic recession and sharp political criticism. Nonetheless, the Fed clearly demonstrated that it could control the path of inflation using monetary policy.

However, while Fed Governors agreed that inflation had been too high, the focus was on maintaining Federal Reserve credibility through the management of inflation expectations rather than setting an official inflation target. The concept of “preemption” gained favor, meaning the ability to raise and lower the Federal Funds rate based on expected rather than actual inflation to achieve policy goals. Some Fed Governors began to believe that the addition of an explicit inflation target was needed to make preemption activities effective. The inflation rate was 2.8% when the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee met in July of 1994. Federal Governor Melzer, supported by Fed Governor Broaddus, argued that the markets were uncertain about the Fed’s ultimate aims, and proposed making inflation goals more explicit, “tying ourselves down a bit.” Interestingly, they agreed that a 3% target was too high. Other Fed Governors were skeptical, arguing that the introduction of an inflation target would be too difficult to implement. Fed Chairman Greenspan asked for a formal debate at the January 1995 meeting, with Broaddus arguing for the target and San Francisco Fed Governor Janet Yellen arguing against. No action was taken following the debate. Another formal debate occurred in July of 1996, with the pro-target side evolving from a less than 3% to a 2% inflation target. Still, no explicit target was announced, despite a general warming toward its implementation. Part of this could be the nature of Chairman Greenspan’s reign: he preferred that Fed business and discussions be very secretive as he wanted maximum flexibility to initiate Fed policy as merited. In fact, investors would carefully examine the thickness of Mr. Greenspan’s briefcase in hopes of guessing what actions the Fed would take on FOMC meeting days!

But the world changed, at least regarding prevailing inflation rates, from the late 1980’s-mid-1990’s (3.5-5% inflation rates) to the latter 1990’s through the late 2010’s (1-2% inflation rates). In October of 2003, Fed Governor Ben Bernanke questioned whether the public and the financial markets truly understood the Fed’s implicit inflation objective. He introduced the Optimal Long-run Inflation Rate (OLIR) to support more efficient pricing (especially for long-term bonds), reduce inflation risk for the financial markets and stabilize long-term inflation expectations more broadly so that short-term adjustments would be more effective. He also proposed that the OLIR target be 2% as it was “the lowest inflation rate for which the risk of the (Federal) funds rate hitting the lower band appears acceptably small”. The “elephant in the room,” as it had been for many years, was the potential damage to the employment mandate should the price stability mandate (i.e., rigid adherence to the 2% target) be prioritized. The FOMC remained split on the issue and further debates focused on a range around a target (1% + or – 1%, 1.5% + or – .50% were proposed, for example). Some still argued against a target, suggesting that it would not improve the long-term outcome.

In 2008-2009, the “Great Recession” ravaged the economy and the markets. Price deflation became a bigger worry. Under Chairman Bernanke, the Federal Reserve implemented “QE2” monetary stimulus but also revived the explicit inflation target idea, anticipating that quantitative easing would eventually revive inflation. By late 2011, the majority of Fed Governors supported an official target, although the preference was that it be flexible. Finally, in the beginning of 2012, the Fed approved the “Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Strategy” which introduced an explicit 2% inflation target, using year-over-year PCE as its measuring stick. Notably, a specific target for Maximum Employment was not set. Somewhat surprising was the lack of an inflation range despite previous support. The context explains that omission at least partially: operating in a disinflationary or even deflationary environment at the time, a specific target seemed to give the Fed more room to be expansionary (i.e., a range would not appear as dovish when inflation was barely above zero). In addition, a range could imply Fed satisfaction with any inflation rate within the range, which could be false.

Over a decade later, the Federal Reserve continues to adhere to the 2% inflation target, which has been very difficult to achieve with the distortions, fiscal, monetary and economic, that arose because of the pandemic. As mentioned before, the Fed has tasked itself with periodically reviewing the effectiveness of its communication, strategy and policy tools. As El-Erian suggests, perhaps it is time to carefully analyze whether the fixed 2% inflation rate remains relevant given the momentous changes in the world and US economy since 2012.

Sources:

https://ycharts.com/indicators/us_core_pce_price_index_yoy

The opinions expressed in this Commentary are those of Baldwin Investment Management, LLC. These views are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions, and no forecasts can be guaranteed. The reported numbers enclosed are derived from sources believed to be reliable. However, we cannot guarantee their accuracy. Past performance does not guarantee future results. We recommend that you compare our statement with the statement that you receive from your custodian. A list of our Proxy voting procedures is available upon request. A current copy of our ADV Part II & Privacy Policy is available upon request or at www.baldwinmgt.com/disclosure.

Susan Berry-Gorelli, Chief Executive Officer

Susan Berry-Gorelli also is the Director of Research and a Portfolio Manager of Baldwin Investment Management. She has over 30 years of individual and institutional investment and risk management experience in the financial services industry. Susan attended The College of William and Mary and the University of Delaware, earning a B.A. in Economics and History, Summa Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa. She is the Board Vice President of the Colonial Theatre in Phoenixville, as well as serves on the finance committees of the French and Pickering Conservation Trust and the Whitemarsh Boat Club.